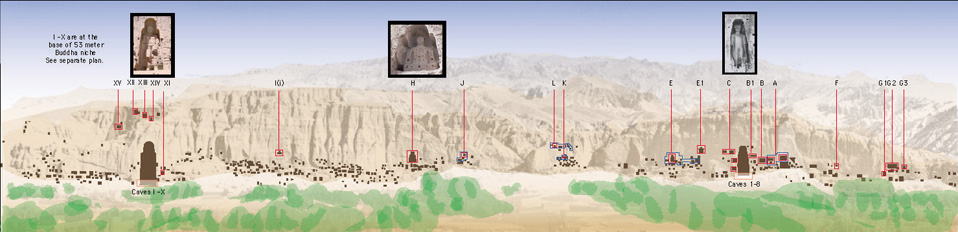

Images of The Buddhist Caves of Bamiyan

Photographic Overview of Bamiyan

download large image (3,563 x 865/ 8.82mb) © Graphic by John C. Huntington. Based on an original photograph.

© Graphic by John C. Huntington. Based on an original photograph.Numbering and lettering system from Goddard, Goddard, and Hackin in Les Antiqués Bouddhiques de Bamiyan (1928); Zemaryalai Tarzi, L'Architecture et le Décor Rupestre des Grottes De Bamiyan (1977).

An Introduction to the Buddhist Caves of Bamiyan:

click here to view a map of Afghanistan The Buddhist art of the Hindu Kush mountain region, of which the Bamiyan Valley is a part, represents the final flowering of Buddhism in Afghanistan. The kingdom of Bamiyan was a Buddhist state positioned at a strategic location along the trade routes that for centuries linked China and Central Asia with India and the west. Bamiyan served as an important monastic and spiritual center, as well as a hub of intense commercial activity. The site was constructed between approximately the fifth and ninth centuries A.D. during a distinctive phase in the history of Buddhist art, a period of intense cultural and religious exchanges between east and west, and a time of great cultural change within Buddhism itself. Bamiyan served as a ceremonial and spiritual center that attracted and comforted crowds of pilgrims and merchants traveling between Central and South Asia.(1) The noted Chinese monk and traveller Hsuan Tsang, who visited the site in 634 A.D., reported that it was a thriving center of Buddhism and described in details the ceremonies and rituals he witnessed there.

The Buddhist art of the Hindu Kush mountain region, of which the Bamiyan Valley is a part, represents the final flowering of Buddhism in Afghanistan. The kingdom of Bamiyan was a Buddhist state positioned at a strategic location along the trade routes that for centuries linked China and Central Asia with India and the west. Bamiyan served as an important monastic and spiritual center, as well as a hub of intense commercial activity. The site was constructed between approximately the fifth and ninth centuries A.D. during a distinctive phase in the history of Buddhist art, a period of intense cultural and religious exchanges between east and west, and a time of great cultural change within Buddhism itself. Bamiyan served as a ceremonial and spiritual center that attracted and comforted crowds of pilgrims and merchants traveling between Central and South Asia.(1) The noted Chinese monk and traveller Hsuan Tsang, who visited the site in 634 A.D., reported that it was a thriving center of Buddhism and described in details the ceremonies and rituals he witnessed there.

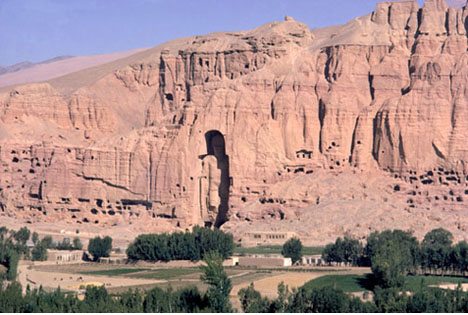

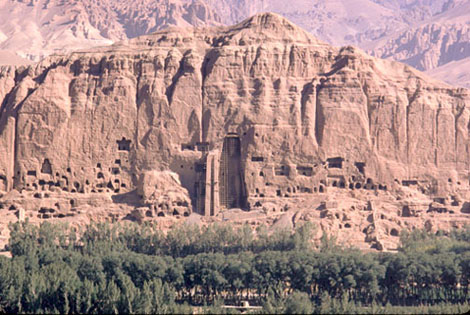

During this extended period of Bamiyan's Buddhist floresence two massive Buddha images were carved out of a high stretch of cliff facing the widest part of the valley. These colossal images are the largest Buddhist sculptures in the world. The greater of the two images stands 53m/175 feet in height at the western end of the cliff-face; the second massive Buddha, at the eastern end of the cliff, is some 35/120 feet tall. All along the cliff face between these monolithic images are carved hundreds of caves of varying size used as chapels for both private and communal worship. Ambulatories, off of which are further rock-cut chapels and image-niches, surround the larger Buddha at the level of his feet and again at the level of his head high up the cliff face. Most of the rock-cut chapels and ambulatories at Bamiyan are covered with paintings over plastered walls that display an incredibly rich, varied, and important body of early Buddhist painting.

The Bamiyan style area derives from the artistic traditions and iconography of both India and Central Asia. Generally speaking, the compositions and stylistic techniques displayed in the paintings at Bamiyan and neighboring sites consist of numerous separate figures represented frontally as iconic forms, rather than within narrative scenes. Buddhas and bodhisttavas painted on the walls and ceilings at Bamiyan convey a vision of the Buddhist universe rather than events and moments in ordinary historical time.

The Bamiyan style area derives from the artistic traditions and iconography of both India and Central Asia. Generally speaking, the compositions and stylistic techniques displayed in the paintings at Bamiyan and neighboring sites consist of numerous separate figures represented frontally as iconic forms, rather than within narrative scenes. Buddhas and bodhisttavas painted on the walls and ceilings at Bamiyan convey a vision of the Buddhist universe rather than events and moments in ordinary historical time.

Each of the multitude of caves and niches at Bamiyan, including those which house the colossal Buddha figures, can be considered a complete and unified composition in which painting and sculpture work together to form a single symbolic configuration.(2) At the center of each of these configurations is a sculpted Buddha form, usually presented at ground level on the north wall. Surrounding this figure on the walls and ceiling of each cave are innumerable painted images of further Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other heavenly figures. The sculptured Buddha figures seem originally to have been painted, and are located in an axial and symmetrical position in relation to the paintings. The wall paintings thus appear to surround the central figure in numerous concentric circles or in vertical rows that in both cases suggest a mandala, a conceptual representation of the Buddhist universe. The ceilings in particular are transformed into a "dome of heaven" through the manipulation of repeated Buddha forms around the central figure. Together, the wall and ceiling paintings work with the sculpture to create an entire heavenly environment, a symbolic representation of the universe.

(1) Deborah Klimburg-Salter, 9-10.

(2) Deoborah Klimburg-Salter, XX